By LEWIS JOHNSON – Co-Chief Investment Officer | December 15, 2016 “Confused sea conditions occur as a result of major shifts in wind direction that occur quickly. This causes waves coming from differing directions, resulting in waves that are irregular and unpredictable.”

– Franklin D. Roosevelt

?David Pascoe

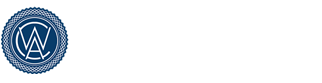

Waves on the open ocean come in different sizes and configurations. The smallest perceptible waves are officially, on the sea state scale, called “glassy.” The largest waves fall under the aptly-named category of “phenomenal” and tower over 46 feet. These names help mariners describe the height of the waves that they face on the open ocean.

There is another wave scale that is equally important for those who hazard the sea. This one describes the character of waves. Not their height but their organization, or – more precisely – their lack of organization. The most volatile of all wave environments is that of “confused” seas. In this environment waves seemingly pound in from all directions, at random and irregular intervals, presenting one of the most profoundly challenging environments for any mariner to navigate.

We suspect that we may soon find ourselves in the financial equivalent of confused seas. Allow me to explain.

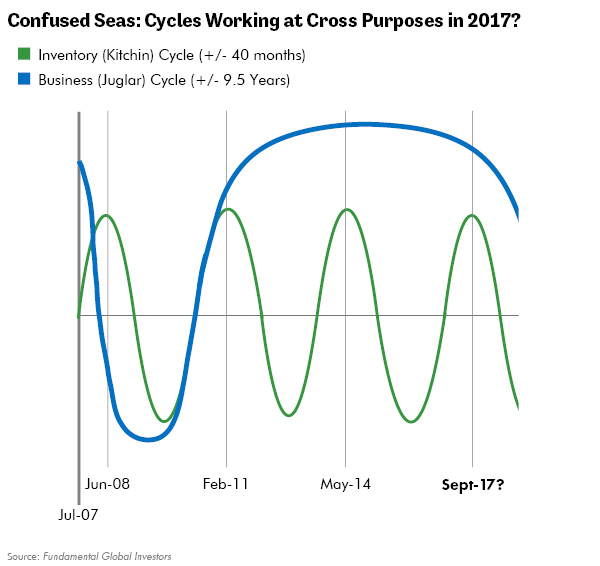

Markets are enjoying the improving fundamentals that come with the restocking phase of the inventory cycle, as we recently outlined (Bearish to Bullish: Opportunities in Steel, November 30, 2016). This cycle, which expresses itself globally across many asset markets, is best observed in the steel market. This improvement should continue until the cycle peaks, perhaps as early as the first half of 2017, but with increasing odds of a downturn as we get deeper into 2017. So, for now, this is good news and it may get better still. This improvement is the action of one wave, the inventory cycle wave, and make no mistake: it is powerful. In fact, through bitter experience painfully earned, I have come to realize that this cycle is the dominant one in the market – even though it is the shortest.

Rarely do cycle-ending, materially negative things happen when the inventory cycle is rising. This is true for a few important reasons. Demand in the inventory upcycle feels stronger than it really is due to the building of speculative inventories. These are the times when growth is often better than expected. Conversely, most painful outcomes in the market spring forth during the down phase of this cycle, when speculative buying vanishes and is replaced first by the ominous pause of caution, and then panicked liquidation of excess inventories.

This kicks off the opposite reaction, the down phase of the inventory destocking cycle, whose end result is worse than expected demand. Oftentimes, this period of stress is when the weak link in the chain breaks. The U.S. stock market has a near 90% correlation with industrial production (monthly since 1970), so it should come as no surprise that inflections in industrial production also tend to be stock market and credit market inflections.

Below, for illustrative purposes, I recap the example of confused seas from 2007 and 2008 and what they may teach us about 2017 and 2018.

Trading the Global Financial Crisis: The Paradox of a Rising Inventory Cycle and a Falling Business Cycle. Might the Past be Prologue?

After preparing for years for what would eventually be known as the Global Financial Crisis, imagine my shock in late 2007 when I discovered that an inventory restocking cycle had just kicked off into the very peak of the business cycle and the start of a financial crisis! It was not the beginning that I had expected. Far from it.

The image below shows the position and action of these two cycles in 2007 and 2008. In disbelief, I had to curb my pent up bearishness for the day when the force of the inventory upcycle was spent and both cycles would join forces and decline together. This would happen in the back half of 2008 and terror followed in its wake.

The scrap steel market, as always, was the tell. Prices in late 2007 began to rise in the U.S. and held every prospect to shoot higher still as the prices of substitute products skyrocketed overseas. This surprising price action caught steel buyers unprepared. After an initial phase of disbelief at the exploding prices, buyers scampered to secure a comfortable level of inventories. Such additional speculative demand made a strong market even stronger. This was broadly supportive of improving U.S. and global industrial production, and was displayed most prominently in the volatile steel markets.

Scrap steel prices spiraled to new all-time highs in May and June of 2008 – months after Bear Stearns had been rescued and almost a full year after U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson made his infamous comments, quoted at the beginning of this research, marking the peak of the business cycle in mid-2007. So, while our credit markets lurched towards the worst downturn since the Great Depression, a speculative inventory accumulation boom was underway in the commodity markets. The cross-currents from these confused seas proved challenging to investors before the two cycles joined forces in a virulent downcycle that would shake the world in late 2008.

Now, as we approach 2017, scrap steel prices are racing higher, again, for good reasons. Despite all of the long-term and unanswered challenges facing the over-indebted world, this is not the time for these problems to unleash the full power of their pent up fury.

We can reasonably expect this to change, with startling alacrity, when the inventory cycle turns from rising to falling. At the time when these two cycles unite, and head downward together, we can expect a one-sidedly negative investing environment to prevail. All of our long work, preparation, and dedicated research on these issues pays off then. Those are not the environments where you can profitably learn as you go. You are either ready for them or you are not.

Business Cycles are Credit-Driven Investment Cycles. The Credit Markets Will Announce Their Arrival

These pages have long outlined our concerns about what we suspect may prove to be weak links that may conspire to kill our current business cycle. We will not repeat them at length here but will note them briefly below.

Chief among these are overindebtedness and political turmoil in Europe, the hangover from the world’s biggest capital boom in China, and perhaps a new suspect – the market’s explosive adoption of seemingly innocuous derivatives in the exchange traded fund or exchange traded note markets. I suspect that the vast majority of these financially innovative products are thoughtfully designed and built to last. As we learned from the Global Financial Crisis, however, a small minority of overly-complex yet seemingly-innocuous financial products can go bad and have far-reaching impact on other instruments and markets. Stranger things have happened. The added bonus in favor of such a vector of action is frankly how unexpected it would be. Crises tend to spring forth when asset classes once deemed by all to be perfectly safe prove to be less so.

For Europe, the clearest signposts to watch are the voting that begin in mid-2017 with French elections, German elections in late 2017, and perhaps (finally) an Italian election that will end unelected, technocratic rule. The revenge of the voter may very well prove to be the trigger for profound economic change that rivals the scope of political change they seek.

Other fault lines are already opening in the political turmoil of emerging markets such as Turkey and Venezuela, and in the war on cash in India and China. It’s not a stretch to see how a rising dollar can exacerbate these conditions even while, in the short run, it benefits the U.S. We will be watching the dollar and these other pressure points with interest as the inventory cycle approaches its peak.

Navigating Confused Seas

The first step to navigating confused seas is understanding the underlying cross currents at work that threaten to push us off course. The two conflicting waves right now are the inventory upcycle and an aging business cycle. Just as such conditions are the most vexing for captains on the seas, so too are they for investors in the markets. Our challenge is to use all the tools at our disposal to construct a thoughtful portfolio that can be opportunistic when necessary but never loses its defensiveness when the skies darken. Our goal is to navigate such portfolios into a safe port at the proper time.

We attempt to do this through the ownership of carefully researched stocks and bonds – in the changing combinations that are the most appropriate for our position in the cycle. The challenge before us is to be sufficiently opportunistic to profit from high conviction short-term investments while never losing sight of the long-term imperative of capital preservation. This is the goal of our research and portfolio construction. No one said this would be easy.

The next phase of the cycle may very well prove to be one of the most challenging that we have faced since this bull market began in 2009. The market does not have to follow with precision the average time windows in which such cycles fluctuate. This is not the time to let down our guard. The markets into which we are heading will require a delicate balance of opportunism and caution, and demand the dedication to act and change our minds with swiftness as times demand. The challenges are great but the rewards for success are high.