By LEWIS JOHNSON – Co-Chief Investment Officer | October 5, 2016 “Hell is truth seen too late.”

-Dorothy Parker

-Hobbes

There is much that we still don’t understand about hurricanes, including their unsettling habit of rapidly intensifying, as Matthew recently did, exploding exponentially in power from just a simple tropical storm to a monster Category 5 hurricane in less than 36 hours. In fact, Matthew experienced one of the fastest and strongest intensifications on record. The process by which this happens is still a mystery. No one forecasted it. It just happened.

Hurricanes are not the only wildly destructive storms that may intensify literally overnight. When weakness engulfs the share prices of large and highly leveraged banks whose enormous balance sheets make them vital to the health of our interconnected global markets, financial storms can erupt seemingly out of nowhere. This disquieting thought runs through my mind as I watch with growing alarm the ongoing collapse in the share price of DB and the accelerating weakness in other thinly capitalized European banks.

Those who successfully navigated the 2008 Global Financial Crisis can never forget how quickly and implacably the crisis spread, confounding the ability of most to forecast its direction and intensity. What we learned then was to expect the unexpected and to stay laser focused on indicators of credit health. They shone a wan light on a very narrow path forward during those dark and challenging days.

Old habits are hard to break. Never does a day go by when we do not closely examine the credit markets. For that reason, beginning in mid-2014, this publication identified early and has been commenting regularly upon the re-emergence of financial weakness in Europe. In the following paragraphs, we outline the spreading credit weakness in Europe, which is also, partly, an explanation of why the Fed has been so slow in raising interest rates.

How did it come to this?

Beginning in May of 2014 (“Big Problems Start Small,” May 14, 2014) we highlighted growing credit stress in Greece, suggesting Europe was the weak link in the global credit markets. Other research would more fully develop this theme, such as February 2015’s research on the dangers of contagion, (“Greece: The Bank’s Problem?,” February 11, 2015), which outlined our fears that credit weakness could extend outside Greece’s credit markets:

Contagion – forced selling and extreme price weakness – is a low probability but high expected value event. Simply put, contagion has only a small chance of taking place but should it do so the outcome would be extremely negative. One analogy might be the consequences of playing a game of Russian Roulette with only one bullet placed in a gun with 100 chambers. Ninety-nine chambers of the gun are empty. There is “only” 1/100 chance that the bullet is in the “wrong” chamber, but should it be so the consequences are fatal!

We went on to outline why Europe was experiencing these credit problems:

Europe in many ways never really addressed its banking and financial problems. Our banking regulators in the U.S. forced our banks to recapitalize and de-lever by issuing equity. Many European banks never did so and remain much more highly leveraged than their American counterparts. For instance, most U.S. banks hold $1 in reserve for every $12-16 of assets that they own. In Europe it’s not unusual to see leverage ratios that are far higher, with $1 in reserve for perhaps $30-50 in assets. This higher leverage means that European banks are far more sensitive than their U.S. counterparts to falling asset prices.

We concluded with why we in the U.S. should care about Europe’s financial problems:

Our modern financial system is an extremely complex web of interlocking debts owed by many entities to a huge array of financial actors and counterparties. Each of these banks and counterparties themselves also in turn owe money to others. Most of the time, thankfully, this complexity does not impact our daily lives. In rare events, such as during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, we come face to face with how complex these markets are.

Europe’s credit problems would indeed spread beyond Greece as we feared, forcing us to return to the theme of contagion again in June of 2016 (“Is Spain the Next Greece?,” June 1, 2016):

Compounding our concerns are lessons learned from the study of George Soros’ “Alchemy of Finance,” where Mr. Soros outlines his theory of reflexivity. This theory describes the behavior of what Mr. Soros calls “far from equilibrium” events where weakness may trigger more weakness in a self-reinforcing and self-referential cycle. Frankly, in our entire investing career, we have never seen a situation more pregnant with reflexivity: highly leveraged European banks, with local sovereign debt as a reserve; and, sovereign governments who – due to the rules of the Euro – are unable to print money to backstop their financial systems. This is an accident waiting to happen.

On June 15th of this year, two weeks before the Brexit vote, we revisited the topic of undercapitalized European banks and the danger they represented (“Brexit: All Eyes on European Banks,” June 15, 2016).

The real issue is debt and how its tentacles spread throughout Europe and indeed the world. The Euro as a currency is not just flawed; it’s also the financial equivalent of a thermonuclear debt bomb. Its many and terrible design failures make it dangerous.

We highlighted the great difficulty of forecasting volatile, reflexive events but asked ourselves the most disturbing question of all, when later in the same publication we noted that “No bank that is too big to fail has been allowed to fail since Lehman. Will that streak end in Europe?”

Credit Weakness Leaps out of the Shadows and onto the Front Page

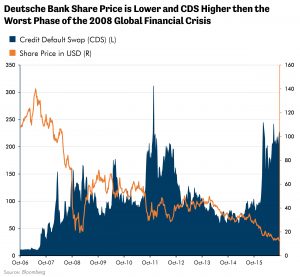

In February of this year, we took a closer look at the potential credit weakness at DB, as we examined the drivers behind the remarkable weakness with which the equity market opened in 2016. Our thesis was the market was dramatically over-estimating the ability of the credit markets to withstand tighter monetary policy threatened by the Fed (“Fed Rate Hikes are a Mistake,” February 24, 2016). In particular we noted that the year began with a near doubling in DB’s five year credit default swaps (CDS) in four weeks from 100 to 264, indicating a rapid intensification of the market’s concerns about DB’s credit quality. CDS are a form of insurance that creditors may buy to hedge against the risk of default. This makes CDS a vital instrument to monitor when it comes to judging a company’s creditworthiness.

DB’s credit default swaps [CDS] certainly seem to be pricing in a material degradation in the market’s estimate of the health of DB’s credit. The Fed seemingly does not share this concern. Whom to trust? No offense to the Fed, but long experience has taught us that we should go with the CDS market… One thing is for sure: clearly the buyers of default insurance for DB are willing to pay a much higher price for this insurance than they were just a few short days ago. Perhaps the Fed should take note. We certainly have.

The CDS market indeed proved to be more insightful than the Fed, which has not made any more moves to raise interest rates – confounding the near universal expectations of “experts.” What they failed to see was simple: they missed the importance of Europe’s weakening credit markets.

We fear that we have not yet seen the end of this trend [European credit contagion] and will be forced to return to this topic in the future. The toxic recipe of high leverage plus an opaque balance sheet plus rising distrust did not play out well for many banks during the last bout of credit stress through which the world suffered. Should we expect a different outcome this time?

The Fed would stumble along for the rest of the year confusing observers with its contradictory statements about what it would do – and ultimately would not do – with short term interest rates. Rather than “blame” the Fed whose members are only human, we should place the burden where it belongs: on Europe’s weak and overleveraged banks. We understood this message loud and clear because, after all, the central organizing theme of our research has been to study overindebtedness and its deleterious impacts.

What Happens Now?

The credit market can lose its faith instantly. In fact, the Latin “credo,” which is at the root of the word credit, means “I believe.” DB’s rising CDS prices suggest that belief in DB’s credit is waning. Remarkably, DB’s CDS are nowabove the most stressed levels of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

This credit weakness has already resulted in DB shares falling 54% in the last year alone. Frankly this could get a lot worse for them, as I explain below.

Should DB find itself in need of a large equity injection, each current shareholder’s pro-rata interest in the company would decline which could result in a lower share price.

During the 2008 Global Financial Crisis in the U.S., highly leveraged Fannie Mae and AIG found themselves in need of more capital than they could raise privately. The U.S. government stepped in, “bailing them out” with much-needed capital and effectively wiping out shareholders.

Despite more than doubling DB’s share count since 2008, neither the credit market nor equity market seem to believe that DB’s footing is as sound as it should be. Could DB’s shareholders wake up to find themselves massively diluted (again)? Is it possible that DB is not the only bank in Europe where shareholders are running such a high risk of dilution? Much will depend upon the next moves in DB’s credit quality. We will be watching events closely.

We cannot neglect the role that government policy decisions may play in DB’s future. DB is such an enormous institution that it no doubt has the full attention of regulators as the coming days unfold, particularly if DB’s share price remains weak. These regulators have proven their willingness to craft creative solutions that “save the day” when pressed to do so. Perhaps the more telling question will be whether they can creatively support DB while not endangering its share price.

In Conclusion

Modern meteorologists have made great strides in understanding and forecasting hurricanes but still have a lot to learn about these killer storms. Sadly our knowledge of financial contagion, which packs all the financially destructive power of a hurricane, leaves even more to be desired.

What we can say for sure is that huge and highly leveraged banks, when stressed, can inflict great losses on their shareholders. Sometimes this trend can spark contagion that rapidly intensifies, amplifying it globally.

We can also say that our central bankers didn’t really “fix” the overindebtedness problem which the 2008 Global Financial Crisis revealed. They have, however, managed to keep anything (since the failure of Lehman Brothers that is) that was “too big to fail” from actually failing. It is this feat that allowed our overindebtedness during this cycle to expand even further – and their unceasing desperation to “do whatever it takes.” Perhaps someone someday will be able to explain how our central bankers logically hoped to fix an overindebtedness problem with more debt.

For many years now, our research has kept us watchful for signs of credit stress. Today’s publication recounts alone more than two years of this effort. We do so because we believe that our greatest commitment to our clients must be to first preserve capital. Weakness always begins in credit, which is why we are ever watchful.

Inevitably, our debt driven problems will return in time. We hope that in sharing with you our research, you may understand our commitment to take the steps we believe are necessary to safeguard wealth when they are most needed, in fact, before they are needed. Thankfully, the market amply provides us with the necessary tools, a thoughtfully researched portfolio of diversified stocks and bonds, that we need to get the job done.