By LEWIS JOHNSON – Co-Chief Investment Officer | July 27, 2016 “To talk of old times with old friends is the greatest thing in the world.”

-A. D. Williams

-Will Rogers

One quirky habit of the classically trained investor, who has spent a lot of time extremely close to both the fundamentals and management teams of the companies we own, is to anthropomorphize the stocks of the companies we have owned and in which we have so long believed. This is especially true when you have been doing this as long as we have, nearly twenty years now. We often slip unknowingly into humanizing these investments and think of them as old friends, especially when the long time we spent together was enjoyable and mutually profitable. After all, we have been through a lot together, we two.

An Old Friend Reappears: Kirby Corporation (KEX)

Kirby is just such an old friend. Kirby first came to our attention in early 2002 during our research at T. Rowe Price on the U.S. fertilizer sector (it’s a long story – more in a later “Trends & Tail Risks”). Kirby’s business consisted of two major lines: 1.) inland barge hauling and 2.) diesel engine services. The inland barge hauling business consisted of a fleet of tug boats pushing tank barges filled with petrochemicals mostly up and down the Mississippi River moving products among the vast network of chemical plants and refineries in the U.S.

The diesel engine service business maintained and serviced both KEX’s extensive tug fleet and other high powered diesel engines. Neither line was a particularly glamorous business. Still though, we liked what we saw.

Like all the best investments, Kirby withstood the rigors of our initial quantitative scrutiny. All the different calculations that we ran on Kirby suggested that the market was undervaluing the stock, on metrics such as: 1.) replacement cost (“From the Analyst’s Toolkit: Replacement Cost Valuation,” June 11, 2014), 2.) peak earnings, and 3.) enterprise value to sales.

The financial measures above, all independent of each other, suggested a compelling “ratio of upside to downside.” In other words, the amount that we stood to win if we were right was far greater than what we could lose if we were wrong. No one knows the future, of course; so our conservative assumption was that our upside price targets had an equal chance of being “right” as our downside targets had of being “wrong.”

What we were confident of, however, was that Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” was hard at work and would eventually balance what was a temporarily oversupplied market. In time, the temporary oversupply in the tank barge market would clear as rapid demand growth soaked up excess supply, and the depressed return on investment from that short-term oversupply would drive returns down and discourage additional investment.

The company’s management graciously offered to host a visit whereby we would tour the assets, meet their team, and get to the bottom of our remaining questions. One sultry Houston day, therefore, found us aboard a tugboat in the Houston ship channel, chatting with one captain about the lonely life of a Mississippi river boat captain. After we docked, a long talk with Kirby’s senior management helped us to understand the great discipline they exercised in allocating capital and the many advantages of their leading market position, such as their unassailable position as the low cost service provider. Furthermore, the more Kirby outgrew its much smaller competitors, the stronger its cost advantage would be from scale and specialization. Appropriately encouraged, we returned to Baltimore to enthusiastically support the purchase of the stock, with an eye to holding Kirby patiently. Kirby had earned its place in the portfolio as a clear market leader, with a sustainable competitive advantage, in an attractive and highly defensible market, all available to us at a discount price during a temporary period of overcapacity.

Patience Can Yield Remarkable Returns

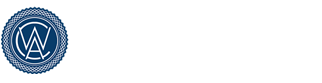

That investment over the next twelve years would grow to be more than 10 times its initial value, which was a compound annual growth rate of 17.9%. Over this time, each dollar that Kirby would invest in its “boring” business, its “return on equity” would average close to 13.6 % per year. How did the lucky owners of Kirby in 2002 achieve a higher rate of return (17.9%) than that earned by Kirby’s own internal investments (13.6%)? Simple: these patient and savvy buyers of 2002 bought Kirby’s assets at a discount, in fact purchasing Kirby from a market so short-sighted that it was happy to give away Kirby at only half of the cost to replace Kirby’s assets.

This value added – from disciplined investing – would earn for Kirby’s patient shareholders an additional return of more than 4.3% per year. Together these two returns – those of the underlying business itself and that from the stock’s remarkable undervaluation – are what made the stock such a homerun. This return was available to investors who did their homework in 2002. If they appropriately valued Kirby’s assets and knew how much the market was undervaluing them, and if they were willing to accept the complete and total lack of “near term visibility” that the market so often craves for a better long term return, then investors were able to earn an additional return of 4.3% per year for twelve years.

This value added – from disciplined investing – would earn for Kirby’s patient shareholders an additional return of more than 4.3% per year. Together these two returns – those of the underlying business itself and that from the stock’s remarkable undervaluation – are what made the stock such a homerun. This return was available to investors who did their homework in 2002. If they appropriately valued Kirby’s assets and knew how much the market was undervaluing them, and if they were willing to accept the complete and total lack of “near term visibility” that the market so often craves for a better long term return, then investors were able to earn an additional return of 4.3% per year for twelve years.

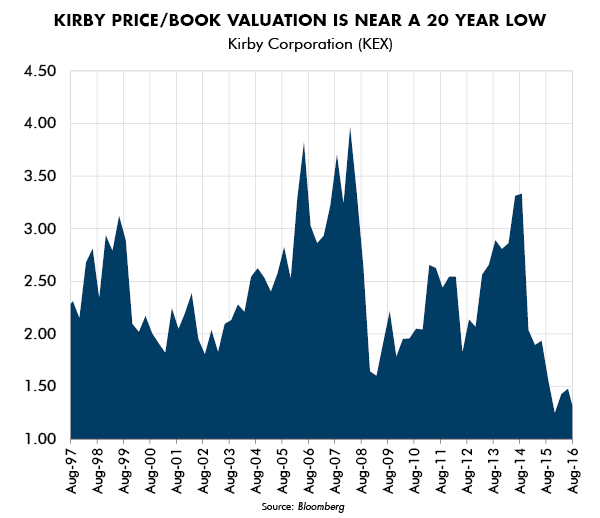

Heeding Jacobi: Kirby and the Art of Inverting

Kirby’s stock is of little interest right now to the great mass of investors who are fixated only upon the near term. Temporary oversupply seems to be well-established in Kirby’s markets. Earnings estimates are falling. When will they bottom? How long might the down cycle last? These “investors” think that investing is a news momentum game: wait until the news gets better and then buy. Right now the news looks just awful. This is reflected in the extremely cheap price to book ratio at which Kirby now trades: at a twenty year low in fact near 1.2x book.

As the chart above demonstrates, in the happier days of a strong upcycle (in 1999, 2007, and 2014), tighter supply relative to demand drove barge rates higher and yielded strong earnings for Kirby. Investors who craved positive reinforcement from happy near term news got plenty of it, and gladly overpaid for this good news by overvaluing Kirby’s assets.

Kirby’s price to book ratio during these times traded at 3.5x reflecting this misplaced enthusiasm, an amount nearly triple that of Kirby’s current valuation. We can reasonably expect that future investors may choose to repeat that error. If so, investors stand to gain solely through the normalization of Kirby’s value as we approach the next peak in the cycle. But when will that be? We have no idea.

Disciplined value investors, however, can overcome this uncertainty by copying the tactics of storied mathematician, Carl Jacobi, who solved some of the hardest problems facing his discipline. His method? Inversion. Put another way, Jacobi believed that the solution to many difficult problems could be found by re-expressing them in an inverse form. Our valuation of Kirby uses this same logic. We use it to stop fixating on what we don’t know about Kirby, and getting the most out of what we do know. Investors did this in 2002 and we have the opportunity to do so again now by solving for what we don’t know: time.

Disciplined value investors, however, can overcome this uncertainty by copying the tactics of storied mathematician, Carl Jacobi, who solved some of the hardest problems facing his discipline. His method? Inversion. Put another way, Jacobi believed that the solution to many difficult problems could be found by re-expressing them in an inverse form. Our valuation of Kirby uses this same logic. We use it to stop fixating on what we don’t know about Kirby, and getting the most out of what we do know. Investors did this in 2002 and we have the opportunity to do so again now by solving for what we don’t know: time.

Using Time and Valuation to Solve for Potential Returns

We can use replacement cost valuation and price/book measures to estimate the price at which Kirby would trade at the next peak. Should Kirby’s valuation mean revert, conservatively, to 100% of the replacement cost of its assets, it would drive the price nearly 90% higher than its current share price. Of course, in prior cycles Kirby’s assets have traded at a far higher valuation, such as the 3.5x book at which the stock has historically traded at prior peaks. If we were to make the undemanding assumption that Kirby’s business is a full seven years away from its next cyclical peak, today’s investors still stand to earn handsome returns of 9.3% per year at our more conservative assumption, or 17% per year should Kirby’s price to book valuation revisit its prior peaks. These are attractive returns, especially in relation to the extremely limited downside from Kirby’s currently depressed valuation. The mid-point of these potential returns is 13%, which matches the stock’s annualized return over the last 30 years.

In Conclusion

James Joyce was right: there are no friends like the old friends. One of our most appreciated mentors at T. Rowe Price many years ago first introduced the merits of Jacobi’s inversion principle. What a valuable lesson this has been. This unique framework – plus the rigors of replacement cost valuation – can help investors overcome uncertainty and, in fact, profit from it using a remarkably simple set of tools.

We draw upon these tools and our long study of cycles to identify opportunities when they arise. Some opportunities that reveal themselves are familiar, such as our old friend Kirby, others arise in the most obscure of places previously unknown to us. But knowledge gained in investing is – thankfully – cumulative. What is today a new face to us will, in the fullness of time, be an old friend in the next cycle. For now, we are settling in patiently with our old friend Kirby, to gladly await the day when its merits, seemingly known only to us now, will be more highly valued by all.